The Length of the Sojourn in Egypt

By Kenneth Griffith and Darrell K. White

Introduction

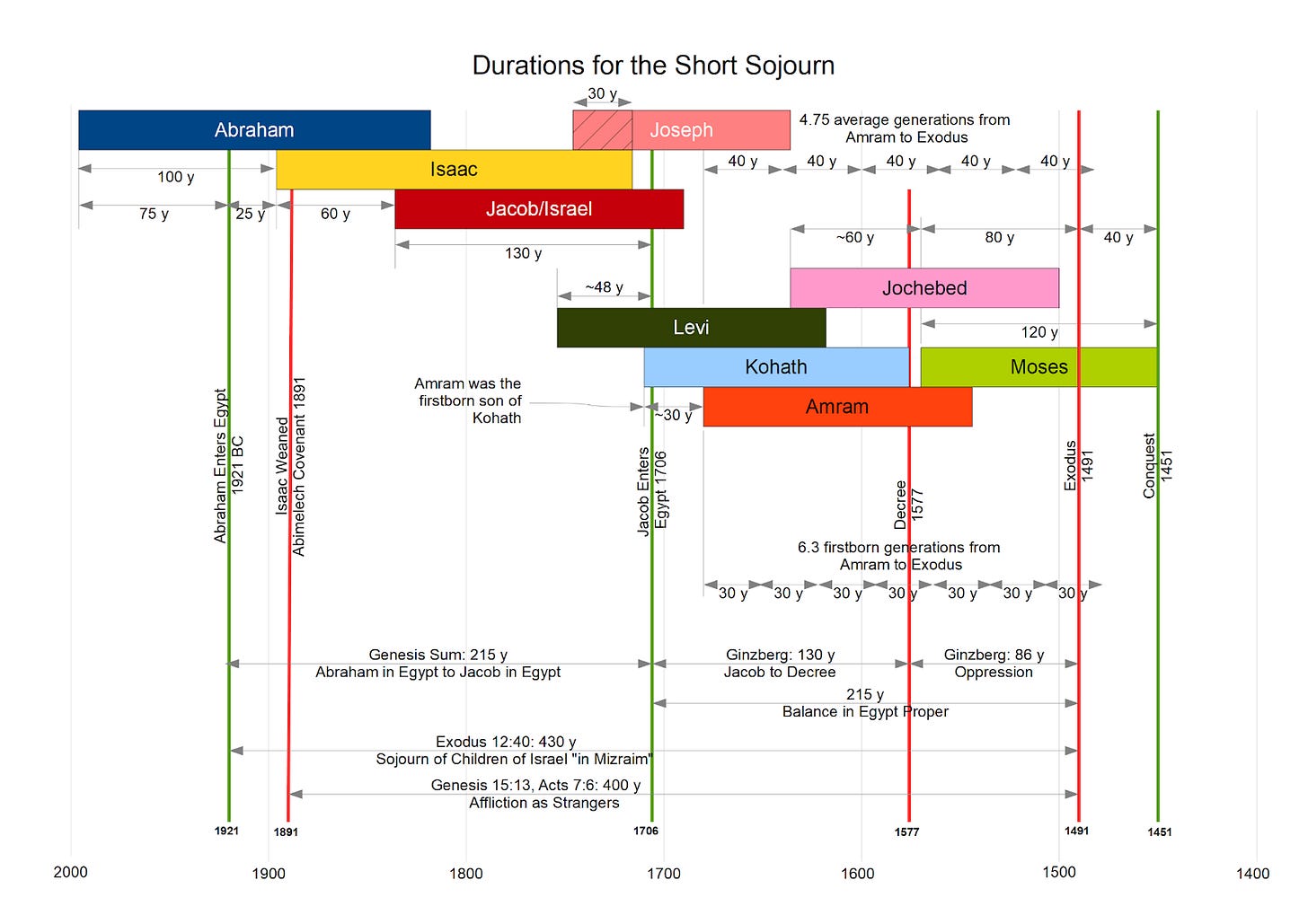

For the past two centuries, Bible scholars have debated the length of time that the Israelites lived in Egypt. The reason for the debate is the wording of the passage in Exodus 12:40. Did the Israelites spend 430 years from Jacob’s entry into Egypt, or were the 430 years from Abraham’s entry into Egypt, as stated in Galatians 3:16-18? In this short paper, we will endeavor to show that the Short Sojourn is the only view that is compatible with Scripture and that it is also supported by two external witnesses.

Over the past few decades, Associates for Biblical Research and several other Christian scholars have promoted the interpretation that the 430 years count from God’s covenant with Jacob to the Exodus, rather than from Abraham’s entry into Egypt until the Exodus (Petrovich 2024). The primary reason for preferring this interpretation has been to fit the conventional chronology of the 12th Dynasty of Egypt, which several scholars recognize as being the dynasty under whom Jacob entered Egypt (Stewart 2008, 80-107; Petrovich 2019, 37). However, those who make this argument have typically resorted to claiming that the genealogies recorded in Exodus and Numbers are missing several generations. Ray makes this argument:

A comparison of various genealogical data reveals that while on the surface, at least, the Levitical genealogy of Moses shows only four generations, other genealogies, such as those of Judah, and the two sons of Joseph, reveal six, seven, and eight generations for the same time period, evidencing that there are some missing generations in the genealogy of Moses. Thus, this genealogy in Exodus 6:16–27 should not be taken as support for the 215-year view. The genealogical data favor, instead, a longer time period.

– (Ray 2007, emphasis added)

Additionally, those like Ray and Petrovich who choose the Long Sojourn in order to match Jacob with the 12th Dynasty of Egypt assume that they know the chronology of Egypt better than we know the chronology of Scripture. If we presuppose that Scripture is chronologically accurate and are open to the possibility that it is the accepted chronology of Egypt that is mistaken, then the problems are easily resolved.

Though this paper primarily critiques the arguments of Petrovich and Ray, Petrovich at least holds to the primacy of Scripture over Egyptian chronology:

The cart should not be trusted to pull the horse. The issue must be solved within the disciplines of biblical studies first, because there cannot be two or more lengths of the sojourn, two or more exodus dates, or two or more exodus pharaohs. As Benware rightly cautioned, the declarations of Scripture must provide the primary evidence to determine these events, and only then can ancient historical evidence be consulted to add flesh to the skeletal structure.

– (Petrovich 2019, 23)

Having established that Scripture must dictate chronology, let’s consider the passages and Petrovich’s interpretations of them.

Correctly Parsing Exodus 12:40

Now the sojourn of the children of Israel who lived in Egypt was 430 years. (Exodus 12:40 )

The word translated as “Egypt” in most English Bibles for this verse is “Mizraim”, but the LXX says, “Egypt and Canaan.” Petrovich argues that since the word in the Masoretic Text is “Mizraim,” the 430 years had to be entirely spent in the territory that we know today as Egypt, and therefore the LXX translation “Egypt and Canaan” was a corruption in the Greek text (Petrovich 2019).

However, Petrovich treats the question as being only whether or not the words “and Canaan” were in the original Hebrew text, rather than considering the geographical possibility that Mizraim could mean “Egypt and Canaan” Petrovich concludes:

While these texts could preserve correctly the inclusion of Canaan as one geographical locale for the sojourn, the MTʼs reading possesses substantial authority, and only with great caution should it be overruled. Due to the strength of the double tradition of the MT and the Dead Sea Scrolls, external evidence favors the reading without Canaan.

– (Petrovich 2019, 29)

While the question of whether “and Canaan” was included in the original Hebrew is certainly the first question that should be asked, that question alone cannot ultimately determine the passage’s meaning. We must go on to ask what the original Hebrew passage meant when it was written, and why the LXX translators might have substituted “Egypt and Canaan” for the word “Mizraim.” Petrovich prematurely concludes the matter after answering only the first question, and by doing so, he misses the forest for the trees.

The second question we should be asking is:

What was meant by the word “Mizraim” in the original text?

The place to begin is to let Scripture define Mizraim for us:

Mizraim begot Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, Pathrusim, and Casluhim (from whom came the Philistines and Caphtorim).

– (Genesis 10:13-14 emphasis added)

Scripture defines the word Mizraim in Genesis 10 as the tribes descended from Mizraim. When Abraham entered Canaan, the southern half was ruled by the Egyptian Philistine tribe, who were of the house of Mizraim.

Genesis 21 records two major events that appear to have occurred in the same year: the weaning of Isaac and Abraham being forced to make a covenant with Abimelech, the Philistine. Both events involved persecution from the house of Mizraim.

When Isaac was weaned around age five, he was mocked by Ishmael, the son of the Egyptian woman, which was highly symbolic. However, the actions of Abimelech the Philistine were more materially significant. The Philistines filled Abraham’s wells with rubble and forced him to enter a covenant with them as the subordinate party. Thus Abraham found himself as a vassal under the authority of Abimelech, king of the Philistines, who was of the house of Mizraim, and probably a vassal to the King of Egypt.

The third question we need to ask is:

Why did the LXX translators substitute “Egypt and Canaan” for “Mizraim” in the original Hebrew text?

A reasonable answer to this question is that by the time the LXX was translated, circa 260 BC, Egypt and Canaan were understood by the Greeks (for whom the LXX was translated) to be separate polities. Therefore, the phrase “Egypt and Canaan” is the Septuagint translation of the meaning of “Mizraim” from Abraham’s day into words the Greek audience understood in the third century before Christ.

When Abraham dwelt in Canaan, the region was effectively ruled by the 4th dynasty of Egypt, and when Jacob went down to Egypt, Canaan was ruled by the 12th and 13th Dynasties, as evidenced by a monument found in Byblos of a governor appointed by Neferhotep I of Dynasty 13. Senusret III of Dynasty 12 is also said by Diodorus to have placed a college of astronomer priests on the Euphrates after he conquered the Levant (Diodorus 1935, Book I.28.1), which indicates the Egyptian 12th Dynasty viewed the Euphrates as their northern border. Egyptian Kings would continue to claim the land of Canaan and Syria to Carchemish until Necho II of the 26th Dynasty, about 1,300 years after Abraham’s time (Jeremiah 46:42), and even further by the Ptolemaic Egyptians down to the reign of Cleopatra, who died in the reign of Caesar Augustus.

The view that Mizraim in Exodus 12:40 refers to both Philistine Canaan and Egypt proper is supported by Galatians 3:16-18:

Now to Abraham and his Seed were the promises made. He does not say, “And to seeds,” as of many, but as of one, “And to your Seed,” who is Christ. And this I say, that the law, which was four hundred and thirty years later, cannot annul the covenant that was confirmed before by God in Christ, that it should make the promise of no effect. For if the inheritance is of the law, it is no longer of promise; but God gave it to Abraham by promise.

This passage places the giving of the Law at Sinai 430 years after some event in Abraham’s life, most likely the first covenant when he was told to go to Canaan. Galatians explicitly states the covenant at the start of the 430 years was with “Abraham and your Seed,” but goes on to specify that the Seed “is Christ”.

Petrovich contradicts Paul’s identification of the Seed, by arguing the Seed, and therefore the start of the sojourn, refers to Jacob (Petrovich 2024, 8). However, Abraham is mentioned by name in the verses before and after the 430-year duration in the Galatians passage, and Paul himself explicitly states in that passage that the Seed refers to Christ, and therefore obviously not Jacob.

Since the law was given on Sinai the same year as the Exodus, this places the promise to Abraham 430 years earlier, not over 645 years earlier as required by the Long Sojourn.

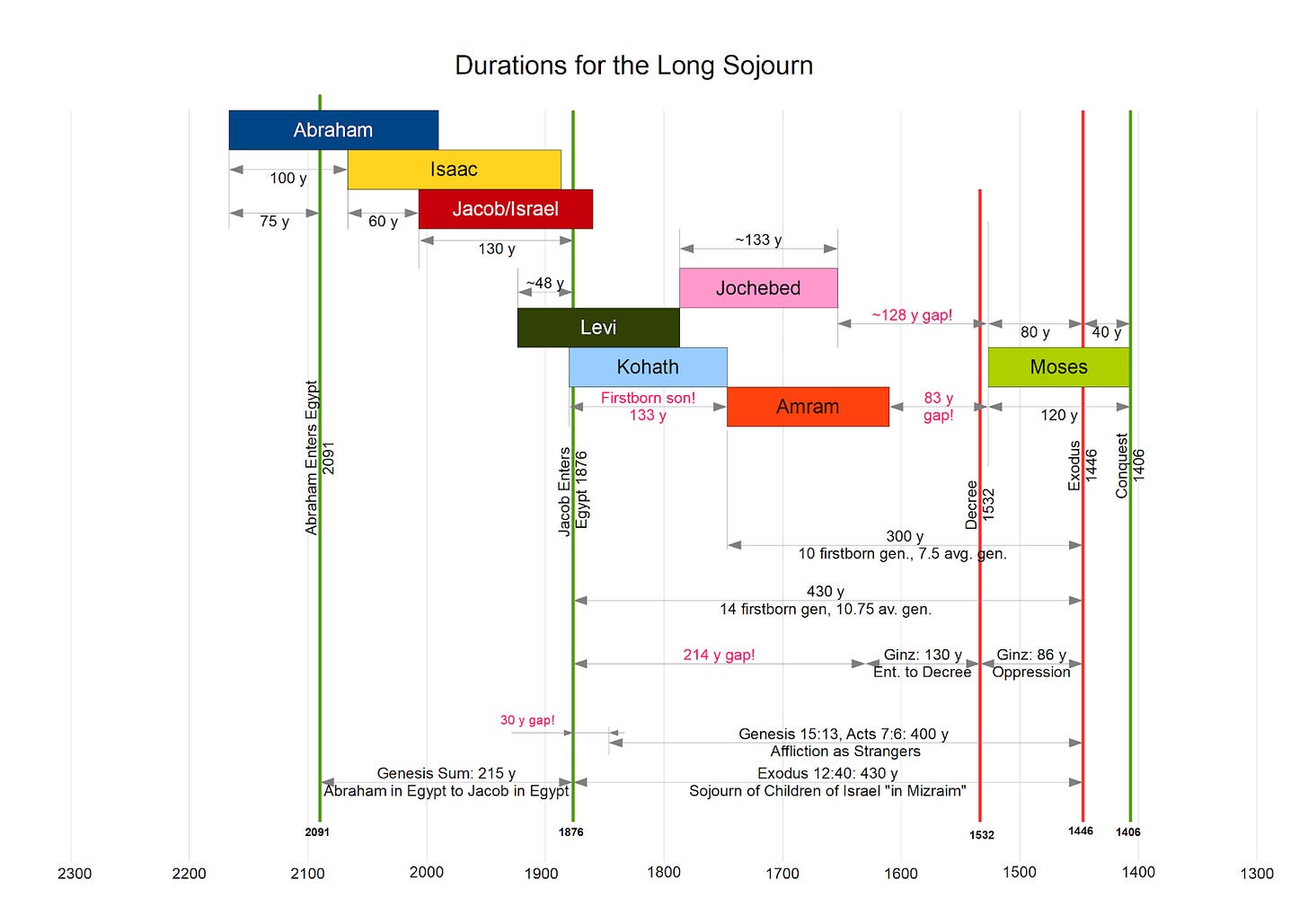

The problem with arguing 400 or 430 years of sojourn from Jacob’s entry based on a strictly literal interpretation of Exodus 12:40 is that it contradicts Galatians 3, and it also creates chronological impossibilities in the lineage of Moses, which is already near the threshold of impossibility even with the shorter 215-year sojourn from Jacob’s entry.

Four Generations from Levi to Moses

The Bible chronology is explicit:

25 years from Abraham’s first visit to Egypt until the birth of Isaac (Gen 12:4; 21:5); plus,

60 years to the birth of Jacob and Esau (Genesis 25:26); plus,

130 years of Jacob’s life before meeting Pharaoh (Genesis 47:9); gives:

215 years from Abraham crossing the Euphrates to Jacob meeting Pharaoh

For the balance of the sojourn, we have three or four generations from Levi to Moses on his father’s and mother’s sides. We don’t know the ages at which the fathers sired the sons, but if we add them all, we get the maximum possible duration of the sojourn from Jacob’s entry date.

And the years of the life of Levi were one hundred and thirty-seven. The sons of Gershon were Libni and Shimi according to their families. And the sons of Kohath were Amram, Izhar, Hebron, and Uzziel. And the years of the life of Kohath were one hundred and thirty-three. The sons of Merari were Mahli and Mushi. These are the families of Levi according to their generations. Now Amram took for himself Jochebed, his father’s sister, as wife; and she bore him Aaron and Moses. And the years of the life of Amram were one hundred and thirty-seven. (Exodus 6:16-20)

Kohath was already born prior to entering Egypt (Genesis 46:11) and was probably 5 or 6 years old unless he and his younger brother were twins. To grant that they were twins born the year of the migration gives the most time to the Long Sojourn.

133 years of Kohath’s life; plus,

137 years of Amram’s life; plus,

80 years of Moses’s life before the Exodus; totals:

350 years Maximum in Moses’ male line, assuming conception in the year of the death of the father for each generation.

We conclude from this passage alone that claiming 400+ years from Jacob to the Exodus explicitly contradicts Scripture unless we grant Ray’s assertion that Moses left out several generations of his own family history when he wrote the book of Exodus. Followers of the Documentary Hypothesis assert that Moses was not the author of Exodus (Dozeman 2010, 1-11), though that claim directly contradicts Scripture (Exodus 24:4). If Moses did omit some generations, then the included ages of only some of his ancestors are rendered useless information to us.

On the mother’s side, this duration is also limited. The fact that the mother of Moses, Jochabed, was Levi’s physical daughter also makes the 430-year sojourn from Jacob’s entry impossible.

The name of Amram’s wife was Jochebed the daughter of Levi, who was born to Levi in Egypt; and to Amram she bore Aaron and Moses and their sister Miriam. (Numbers 26:59)

Levi was older than Joseph, and we know Joseph’s age when his father came down to Egypt. Joseph’s age when Jacob arrived was 30 + (9 or 10), therefore, at a minimum, 39 or 40 years of Levi’s life preceded the family moving to Egypt. Joseph was born shortly before Jacob left Haran, and given that Rachel gave birth (and died) when he arrived in Shechem, that suggests Joseph was about 5 years old at that point. Jacob’s marriage was 20 years before he left for Haran (Genesis 31:38), and Levi was third-born and thus was born no less than 7 years after Jacob got married. 20 minus 7 minus 5, gives an 8-year estimated age difference between Joseph and Levi. Therefore, about 48 years of Levi’s life preceded Jacob going down to Egypt.

If Levi was 48 when Jacob entered Egypt, then he spent the final 89 years of his life in Egypt, living to 137. Moses was born 80 years before the end of the sojourn. Therefore, assuming that Levi sired Jochebed in the final year of his life, her age at the conception of Moses under the Long Sojourn theory must have been:

430-year sojourn; minus,

89 years of Levi’s life in Egypt; minus,

80 years of Moses’ life before the Exodus; gives:

261 years, the age of Jochebed when Moses was born under the Long Sojourn

We are unaware of any Bible scholars who argue that a woman born later than the fourth generation after the Flood had more than two centuries of fertility. Therefore, the Long Sojourn is also explicitly contradicted by the fact that Levi was the grandfather of Moses on his mother’s side through Jochebed.

Ray tries to get around this by claiming Jochebed was merely a descendant of Levi. Ray’s argument might pass for Jochebed, “the daughter of Levi,” meaning a descendant. However, the phrase “born to” (יָלְדָ֥ה) in the vast majority of cases used in Scripture means the act of birthing the child, never referring to a descendant. Jochebed was Levi’s direct, first-generation daughter. The reason that Levi’s paternity is repeated twice in the text is probably that it seems so unlikely.

Even for the Short Sojourn, the only way Moses could have been Levi’s grandson was if Levi sired Jochebed in Egypt about the age of 123, only 14 years before his death, and Jochebed bore Moses around the age of 60. Jochebed bearing her last child at sixty is reasonable because lifespans were still about 50% longer than the modern average during the sojourn.

Genesis 15:16 says: “But in the fourth generation they shall return here, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.” From Levi to Moses, there were four generations in the male line counted inclusively. Four generations in that era could not have stretched four centuries, based on the recorded ages of the patriarchs.

Ray introduces another argument, saying that the data in Numbers requires that in some family lines, there were 7 or 8 generations during the sojourn.

Further evidence pertinent to the Levi genealogies may be found in the fact that the genealogies of Judah (1 Chr 2:1–20) and Ephraim (Nm 26:35–36; 1 Chr 7:20–27) indicate seven and eight generations, respectively,[xviii] for the same or a slightly lesser time period than that encompassed in the four-generation genealogies of Levi in Exodus 6:16–27 and Numbers 26:57–62. At the very end of each of these other genealogies, we find reference to several contemporaneous individuals from the three tribes. Thus, these more-extended genealogies of Judah and Ephraim would seem to indicate incompleteness in the Levi genealogies.

The problem with Ray’s argument is that Israelite men in that era frequently took additional younger wives in their old age and continued to have children, like Abraham did with Keturah. Hezron is the most extreme example, who had at least three wives and whose last child was born after he died.

Also the sons of Hezron who were born to him were Jerahmeel, Ram, and Chelubai. … Now afterward Hezron went in to the daughter of Machir the father of Gilead, whom he married when he was sixty years old; and she bore him Segub. Segub begot Jair, who had twenty-three cities in the land of Gilead. … After Hezron died in Caleb Ephrathah, Hezron’s wife Abijah bore him Ashhur the father of Tekoa.

– (1 Chronicles 2:9-24, emphasis added)

Given that they were living 130 to 140 years and came to sexual maturity around age 30, that means an Israelite man in that era could sire children born up to 110 years apart in the same generation.

In the same space of 215 years argued by the short sojourn, there could have been some families that, starting with the generation (grandchildren of Jacob) that entered Egypt, begot seven more generations of the firstborn line in Egypt, for a total of nine generations after Jacob, as seen in the examples given by Ray above.

Ray’s error is to assume that the record of eight generations in one tribe at the Exodus, therefore, requires a longer sojourn than the three and four generations to Moses. However, any population will have a generational average of the dates of the births of all of the children, not just the firstborn. The long generations of Moses, assuming the 215 years of the Short Sojourn, averaged 67.5 years from the birth of the father. If most men sired children from age 30 to 110, as the biblical evidence suggests, the generational average could be as high as 70 years.

The eight-generation families and the three-generation families, like that of Moses, were merely the opposite tails of the bell curve, with the majority being the average somewhere in the middle. Dividing 215 years by an average generation of 70 years comes to just over three generations, plus the already-born generation when Jacob entered Egypt, makes four. If we use a more realistic average generation of 40 years, there were 5.3 generations born in Egypt before the Exodus. Thus, the average number of generations from Jacob across all the Israelite families at the time of the Exodus was probably around four or five. Moses was the youngest of the youngest line from Levi.

Ray also argues that the number of Kohathites recorded as over 8,000 men, shortly after the Exodus, was far too many to have been produced in only three generations from Kohath to Moses.

These families of the Amramites, Izharites, Hebronites, and Uzzielites consisted of 8,600 men and boys (not including women and girls), of which about a fourth (or 2,150) were Amramites. This would have given Moses and Aaron that incredibly large a number of brothers and brothers’ sons (brothers’ daughters, sisters, and their daughters not being reckoned), if the same Amram, the son of Kohath, were both the head of the family of the Amramites and their own father (Keil and Delitzsch 1952b: 470). Obviously, such could not have been the case.

Ray failed to count the extra generations in the line of Amram’s descendants in the eighty years between the birth of Moses and the Exodus.

The census in Numbers 3:28 tells us that there were 8,600 male Kohathites from infant to old age. And the census in Numbers 4:34-37 tells us that the heads of households from age 30 to 50 numbered 2,750. These two numbers also tell us about the fertility of the Kohathites. 8,600, minus 2,750, and divided by 2,750 is 2.12 sons per head of household. The portion of the Amramites being one-quarter of these, the total population of Amram at the Exodus was about 2,150 males from infant to old age. That is the number that the population calculations need to hit.

Read what Scripture says about the fertility of the Israelites:

But the children of Israel were fruitful and increased abundantly, multiplied and grew exceedingly mighty; and the land was filled with them.

– (Exodus 1:7)

This sentence says in four different ways that Israelite fertility in Egypt was extremely high. Benjamin is recorded as having ten sons when he entered Egypt (Genesis 46:21), though he would only have been thirty-five years old. To have so many sons in only five or six years, Benjamin’s father must have given him more than one wife as soon as he reached puberty, which would be consistent with Jacob’s favoritism toward Benjamin. Given their longer lifespan, their practice of polygamy, and lack of birth control, an average of ten children per Israelite man during the time in Egypt seems entirely reasonable, especially if they had low infant mortality.

Numbers 3:19,27 lists Amram twice as the firstborn son of Kohath, whom we earlier calculated was about five years old when he came to Egypt. This suggests Amram was born about 25 years after Jacob’s entry, leaving 190 years for his progeny to multiply until the Exodus. Moses, being born 80 years before the Exodus, was sired when Amram was about 110 years old, by his [presumed] second wife, Jochebed. This assumes that Amram married at about age 30 and had an earlier set of children by his unnamed first wife. None of the geneologies list the children of the fourth generation from Jacob, except for the lines of notable leaders like Moses, Aaron, and Joshua. Therefore, Amram must have had sons beginning around age 30, and his marriage to Jochebed was a second, or third, marriage in his old age.

Assuming Amram began siring children with his first wife at age 30, if she had ten children, half boys, and we use the 40-year average generation, then there were 4.75 generations at the Exodus. Five sons per generation raised to the 4.75 power gives 2,089 male descendants, which is quite close to the target of 2,150 males. However, that calculation only tells us the size of generation 4.75 and does not include the fathers and grandfathers still alive from generations 3 and 4.

125 – Generation 3: 53

625 – Generation 4: 54

2,089 – Generation 4.75: 44.75

2,839 – Approximate Total Male Amramites living at the Exodus

With 5 sons per generation, the required number of descendants was exceeded by 32%. However, we must remember that the boys were killed for at least five years from the Decree to the birth of Moses, which would lower the count.

If the Israelite men were practicing polygamy before the final enslavement, as we know at least some of them did, the same results could have been achieved with only 5 births per woman instead of 10. Ray’s objection is thus reasonably overcome.

The Children of Israel

The Bible is internally consistent. So the question is, why does Exodus 12 say “the sojourn of the children of Israel” was 430 years if it doesn’t solely mean the children of Jacob, the first of whom weren’t even born until nearly halfway through the sojourn?

The passage uses the term seed in the same way that the author of Hebrews argues that Levi was in the loins of Abraham when he paid a tithe to Melchizedek.

Even Levi, who receives tithes, paid tithes through Abraham, so to speak, for he was still in the loins of his father when Melchizedek met him. (Hebrews 7:10)

Of all of the “seeds” of Abraham, only the children of Jacob (Israel) sojourned under the Egyptians for the full 430 years from Abraham’s first visit to Egypt, or 400 years from the start of the persecution when Isaac was weaned. Ishmael and the sons of Keturah left Canaan and, therefore, Egyptian authority. Esau also left Canaan and went to the Southeast side of the Arabah to found Edom, outside of Canaan, and outside of Egyptian authority. Of all the children of Abraham, only the children of Israel sojourned the full 400 years under Egyptian authority. This seems to be why it was worded in that way.

400 Years of Bondage

Genesis 15:13 records God’s prediction to Abraham that his descendants would face 400 years of affliction, and Stephen in Acts 7 records that the bondage and oppression lasted four hundred years. Petrovich rightly observes that the 400 could be intended as a round number:

The exact length of the sojourn should not be sought in Genesis 15:13 because the “400” in this verse was intended to be a rough number, just as was the use of the term “fourth dor ” in Genesis 15:16 (Wenham 1987, 332). Kitchen (2003,355–56) perceptively referred to the predicted 400 years of the Egyptian sojourn as a number that was cast as a round figure and looked into the future, and he argued that the Hebrew word dor, which usually is rendered four “generations” in English translations, actually means “spans,” given that the West Semitic cognate daru was used to denote the seven spans of time that elapsed between the fall of the Akkadian Empire and the accession of Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria (ca. 1800 BC), whose scribes would have measured these spans as totaling between 530 and 730 years.

– (Petrovich 2019, 31)

Petrovich argues a bit too confidently because the 400 years could also be a precise duration, as proponents for the Short Sojourn have long argued (Jones 2026, 55-56). At this point, we will only say that it could be either rounded or precise, and we won’t hold him to the precise duration.

Adherents of the Long Sojourn argue that the 400 years of bondage mentioned by Stephen in Acts 7 must have been entirely in Egypt proper.

And from there, when his father was dead, He moved him to this land in which you now dwell. And God gave him no inheritance in it, not even enough to set his foot on. But even when Abraham had no child, He promised to give it to him for a possession, and to his descendants after him. But God spoke in this way: that his descendants would dwell in a foreign land, and that they would bring them into bondage and oppress them four hundred years. ‘And the nation to whom they will be in bondage I will judge,’ said God, ‘and after that they shall come out and serve Me in this place.’

– (Acts 7:4b-7)

Note that Stephen did not use the word “Egypt” in that sentence or paragraph. When it is understood that Mizraim included the Philistines, the sojourn in the “foreign land” began with Abraham himself, who was a stranger in a strange land with “not even enough to set his foot on” shortly after Isaac was born, as is implied by the next verse:

Then He gave him the covenant of circumcision; and so Abraham begot Isaac and circumcised him on the eighth day; and Isaac begot Jacob, and Jacob begot the twelve patriarchs.

– (Acts 7:8)

Thus, the four centuries of persecution mentioned in Genesis 15:13 and Acts 7:4-7 are chronologically consistent with the Short Sojourn from the weaning of Isaac at age 5 to the Exodus, exactly 400 years later. And the 430 years counted from Abraham’s first entry into Egyptian territory when he was 75 years old. Both durations are precise, and both are internally consistent with the other durations recorded in Scripture.

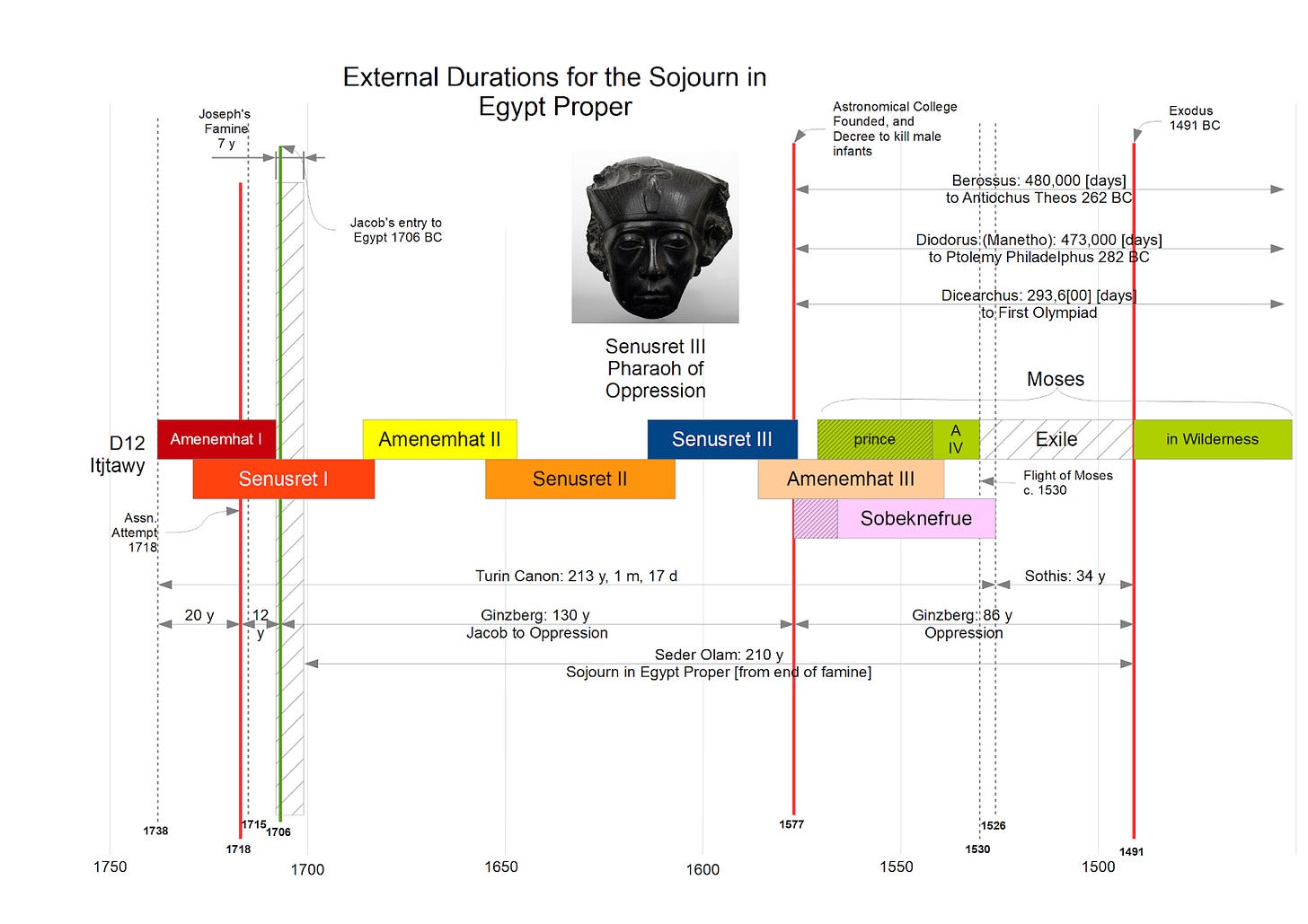

Egyptian Durations

In addition to the Scriptural durations, there is evidence from the Egyptian records that supports the Short Sojourn.

The Turin Canon informs us that the Egyptian 12th dynasty lasted 213 years (Lundström 2025). Stewart argues that an assassination attempt occurred in the twentieth year of its first king, Amenemhat I, which led to the trials of the baker and the butler (Stewart 2008, 80-107). Courville argued that the death of Concharis recorded in the book of Sothis was 34 years after the death of the last queen of Dynasty 12, and that Concharis died at the time of the Exodus (Courville 1971, Vol I, 121-122). If he was correct, the duration from the start of the 12th dynasty to the Exodus would have been 247 years.

Joseph was promoted two or three years after the assassination attempt in the twentieth year of the first king of Dynasty 12, and Jacob entered Egypt 9 or 10 years later in the second year of the famine. Therefore:

213 years of Dynasty 12; plus,

34 years to the death of Concharis in the Exodus; minus,

20 years to the assassination attempt; minus,

2 or 3 years to Joseph’s promotion; minus,

9 or 10 years to Jacob’s entry; gives:

214 - 216 years from Jacob’s entry to the Exodus

Three other ancient sources also give us a precise date for the Pharaoh Senusret III of Dynasty 12 returning from his Asian campaign and sending a college of astronomer priests to the Babylonians on the upper Euphrates (near Haran).

Pliny, citing Berossus and Critodemus, says Babylonian astronomy was improved 480,000 [days] in the past. Berossus dedicated his book to Antiochus Theos, whose reign began in 262 BC. 480,000 days before 262 BC was 1576 BC. (Pliny 1855, Book VII.57.53)

Diodorus wrote that “To Babylon…colonists were led by Belus…and after establishing himself on the Euphrates river, he appointed priests, called Chaldaeans by the Babylonians…; and they also make observations of the stars, following the example of the Egyptian priests, physicists, and astrologers.” 473,000 [days] prior to Alexander (Diodorus 1935, Book I.28.1; Book II.31.9). Assuming his source was Manetho, who dedicated his book to Ptolemy Philadelphus, whose first year was 282 BC, this points to 1577 BC.

Dicearchus placed Sesostris III 293,6[00] [days] before the first Olympiad in 776 BC, yielding 1579 BC. (Spineto 1845, 403, 404)

Figure 3 shows these three durations in the context of the 12th Dynasty. The fact that three durations from different sources and events point to the same year for the founding of the astronomical college by Egyptian Belus, aka Senusret III, around 1577 BC is quite significant.

The year 1577 BC was 86 years before Ussher’s 1491 BC date for the Exodus. This becomes highly relevant when we look at the traditions of the Jews.

Jewish Traditions (Josephus, Seder Olam, and Talmud)

A second external set of testimonies is found in Josephus, the Seder Olam, and the Jewish Talmud.

Josephus states explicitly that the 430-year sojourn began with Abraham.

They left Egypt in the month of Xanthicus, on the fifteenth day of the lunar month: four hundred and thirty years after our forefather Abraham came into Canaan. But two hundred and fifteen years only after Jacob removed unto Egypt; it was the eightieth year of the age of Moses, and of that of Aaron three more. (Antiquities Book II.XV.2)

However, in the previous chapter, Josephus relates that the Israelites labored 400 years under the Egyptians. However, Josephus does not peg the start and end of the four centuries of affliction in that passage; he merely mentions it amid a chapter about the afflictions. Recognizing Philistines as members of the House of Mizraim, this passage is also consistent with the Short Sojourn.

Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews, an English translation of the Mishnah, specifies that the four hundred years of affliction began with Isaac’s birth (Ginzberg 2004, Vol 2, IV.125), but that the duration of the time in Egypt was only 210 years (Ginzberg 2001, Vol 2, IV.145).

The same text states that the decree to slaughter the infants was given 130 years after Jacob entered Egypt (Ginzberg 2001, Vol 2, IV.21). Elsewhere it states that the dominion of the Egyptians over the Israelites lasted only 86 years (Ginzberg 2001, Vol 3, I.27) but that the Israelites had been strangers in the land for four hundred years since the birth of Isaac (Ginzberg 2001, Vol 3, I.28). Thus, in the Jewish tradition, only the final 86 years of the four centuries of affliction as strangers were the Israelites reduced to chattel slaves.

Adding those two durations together, the total sojourn in Egypt comes to 216 years.

130 years from Jacob’s Entry to the Decree to kill babies; plus,

86 years from the Decree to the Exodus; gives:

216 years from Jacob’s entry to the Exodus

Also, the 210-year duration cited above may have been counting from the end of the seven-year famine, which lasted five more years after Jacob entered Egypt.

The 86-year duration is seen to be significant because Sesostris III returned from his Asian campaign and sent the astronomical college to the Euphrates about 86 years before Ussher’s 1491 BC Exodus date.

Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. And he said to his people, “Look, the people of the children of Israel are more and mightier than we; come, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they multiply, and it happen, in the event of war, that they also join our enemies and fight against us, and so go up out of the land.”

– Exodus 1:8-10

The context fits Sesostris III of Dynasty 12 as the king who knew not Joseph. In his Asian campaign, he fought the Edomite and Keturite descendants of Abraham and recognized the Israelites as their kinsmen, and feared they might turn against him. Thus, his decree to enslave the Israelites and kill their sons was most likely given in 1577 BC when he returned from his Asian campaign. This agrees within one year with the Jewish tradition that they served 86 years as chattel slaves. (Figure 1)

Conclusions

We find that two solutions are being proposed, one that breaks the durations and bends the biblical passages, and the other that harmonizes them.

The Solution that Breaks Everything

Advocates of the Long Sojourn, such as Petrovich and Ray, must resort to bending and breaking the other chronological passages of Scripture to force them into their predetermined conclusion of the 430-year sojourn. They claim that Moses omitted generations from his own genealogy and that Paul was speaking of Jacob, not Abraham, even though he explicitly named Abraham twice when speaking of the 430 years.

In doing so, they avoid dealing with the question of what it meant to sojourn as strangers for four hundred years in Mizraim. Petrovich abandons his inquiry after concluding the words “and Canaan” were not in the original Hebrew text. The stated motivation for preferring the Long Sojourn by both scholars is to make the chronology of the Bible fit the accepted chronology of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty.

In our view, this is backward because the true chronology of the 12th Dynasty of Egypt is by no means confidently known. Academics have high, middle, and low chronologies for that dynasty, differing by up to four centuries, which indicates they cannot even agree among themselves. Figure 2 shows that the Long Sojourn produces five gaps with the recorded scriptural and extra-biblical durations.

A Solution that Is True to the Biblical Data

When we interpret the relevant passages of Scripture in such a way that they all agree, the answer becomes clear.

430 years of the sojourn in Exodus 12:40 count from Abraham’s first visit to Egypt, the year that he crossed the Euphrates.

400 years as strangers in Genesis 15:13 and Acts 7:6 count from the birth of Isaac (rounded) or the weaning of Isaac (exact) to the Exodus.

430 years from the promise to the Law in Galatians 3:17 count from Abraham’s first meeting with God at age 75 until the Law was given at Mt. Sinai, three months after the Exodus.

Internal chronological passages indicate that Jacob entered Egypt 215 years after Abraham crossed the Euphrates. Subtracting 215 years from the 430-year duration of the sojourn gives 215 years from Jacob’s entry into Egypt until the Exodus. This agrees with the external durations found in Egyptian records and Jewish historical traditions.

Christian theologians have been aware of this solution since before the time of Bishop Ussher in the 16th century.

In addition to Scripture itself, two sets of external witnesses concur with the Short Sojourn, namely the Egyptian data and the traditions of the Jews. As cited above, we have three precise durations to Sesostris III from the ancient chroniclers that agree with both Ussher and the Jewish traditions, but place Sesostris nearly two centuries later than the lowest accepted chronology for Dynasty 12. A fourth duration from the Midrash, that the decree was given 86 years before the Exodus, ties the other three to the Biblical chronology. Figure 3 shows how the Biblical data and the extrabiblical durations mesh together for the 12th Dynasty of Egypt.

As presuppositionalists, we do not allow extra-biblical sources to dictate our interpretation of Scripture. But when extra-biblical sources agree with an internally consistent interpretation of Scripture, that can be seen as a strong confirmation that the interpretation is correct.

The only internally harmonious interpretation of the relevant biblical passages is that the 430 years of the sojourn of the children of Israel were counted from Abraham crossing the Euphrates at the age of 75. Therefore, Jacob entered Egypt only 215 years before the Exodus.

References

Courville, Donovan. 1971. The Exodus Problem and Its Ramifications. Vol I & II. Loma Linda, California: Challenge Books.

Diodorus Siculus. 1935. C. H. Oldfather, trans. Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dozeman, Thomas B. (editor). 2010. Methods for Exodus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 1959. The Royal Canon of Turin. Oxford: The Griffith Institute. https://pharaoh.se/turin-kinglist-column-7

Ginzberg, Louis. 2001. The Legends of the Jews, Vol I-IV, Gutenberg Project Foundation, Oxford, MS: Gutenberg Project Foundation.

Jones, Floyd Nolan. 1993-2026. The Chronology of the Old Testmament. Green Forest, AR: Master Books.

Lundström, Peter. 2025. Turin King List Column 7. https://pharaoh.se/ancient-egypt/kinglist/turin/column-7/

Petrovich, Douglas R. 2019. “Determining the Precise Length of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt.” Near Eastern Archaeological Society Bulletin. NEASB 64 (2019).

Petrovich, Douglas R. 2024. Resolution of the Exodus 12:40 Textual Variant. Accessed on 1/31/2024. https://www.academia.edu/34278461/Resolution_of_Exodus_12_40_Textual_Variant

Pliny. 1855. John Bostock & H. D. Riley, trans. The Natural History of Pliny. London: Henry G. Bohn.

Ray, Paul J. Jr. 2007. “The Duration of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt” Bible and Spade 20:3. 2007. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3228-the-duration-of-the-israelite-sojourn-in-egypt

Spineto, Marquis. 1845. The Elements of Hieroglyphics and Egyptian Antiquities, London: Printed for C.J.G. & F. Rivington by R. Gibert.

Stewart, Ted T. 2003. Solving the Exodus Mystery. Lubbock, Texas: Biblemart.com, 70-107.